DeployGroundA Framework for Streamlined Programming from API Playgrounds to Application Deployment

Abstract

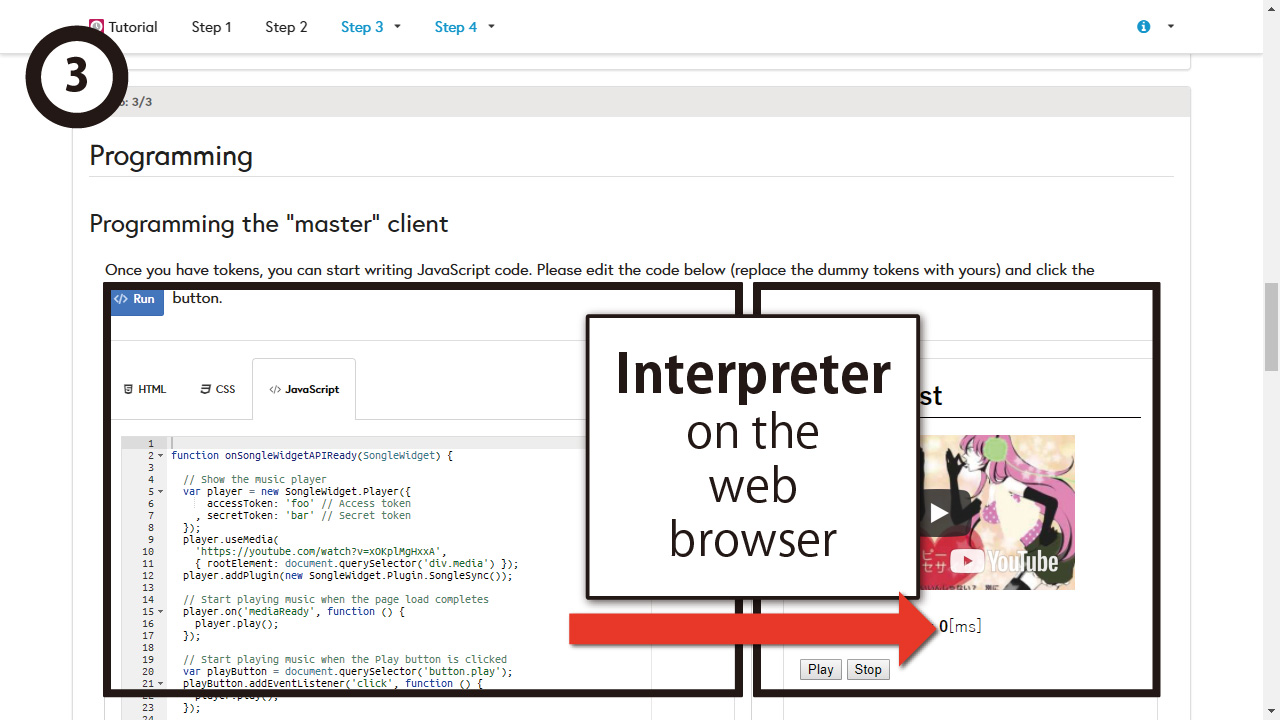

Interactive web pages for learning programming languages and application programming interfaces (APIs), called playgrounds, allow programmers to run and edit example codes in place. Despite the benefits of this live programming experience, programmers need to leave the playground at some point and re-start the development from scratch in their own programming environments.

This paper proposes DeployGround, a framework for creating web-based tutorials that streamlines learning APIs on playgrounds and developing and deploying applications. It has three unique features: a pseudo-runtime environment for a quick response, an adaptive boilerplate for deploying projects, and a reversible software engineering feature for importing deployed projects as example codes.

As a case study, we created a web-based tutorial for browser-based and Node.js-based JavaScript APIs. A preliminary user study found appreciation of the streamlined and social workflow of the DeployGround framework.

Presentation materials

Related Work

Due to the page limit, we needed to omit some interesting prior work from the Related Work section in the paper. The following text provides a more complete introduction to the related work.

A. Coding Tutorials on the Web

In the era when "software is eating the world", there is a massive demand for people who can code. This has resulted in numerous coding references and tutorials available on the web [Kim et al., SIGCSE '17]. In the context of HCI, while there is much work on creating tutorials [Chi et al., UIST '12, Chi et al., UIST '13, Kim et al., CHI '14, Lafreniere et al., CHI '13], there is only a handful of work specialized in creating interactive coding tutorials. Harms et al. explored automatic generation of interactive step-by-step tutorials by transforming each sentence of example codes into a step [Harms et al., IDC '13]. Tutoron [Head et al., VL/HCC '15] allows one to write micro-explanations of code and allows learners to read them automatically inserted next to example code on the web. Codepourri [Gordon et al., VL/HCC '15] allows annotation of the history of program executions through which learners can navigate to learn the program behavior. Our work does not provide tools for creating a new kind of tutorials as these prior works do but instead presents a framework that aims to address limitations of existing web-based coding tutorials for learning APIs.

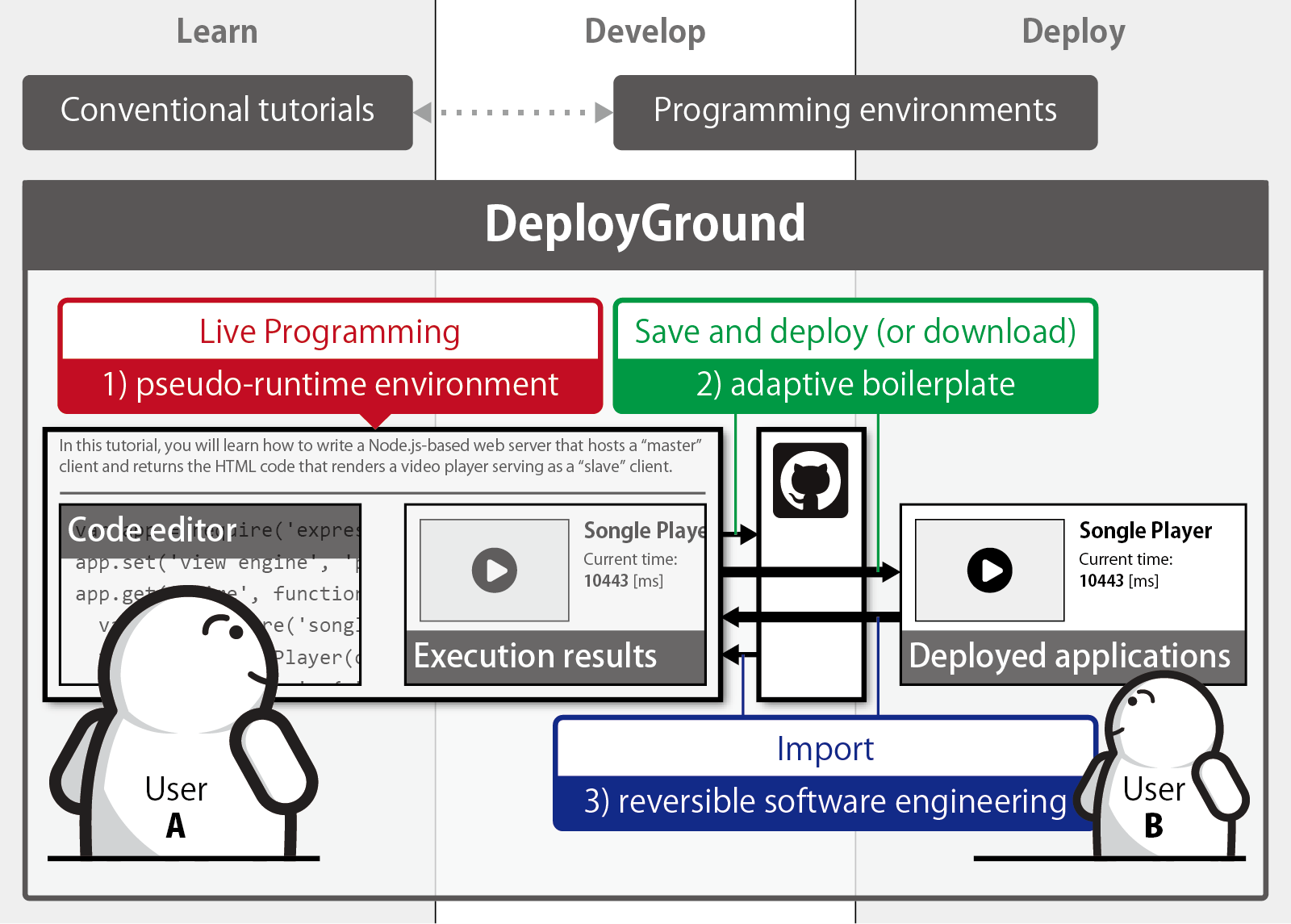

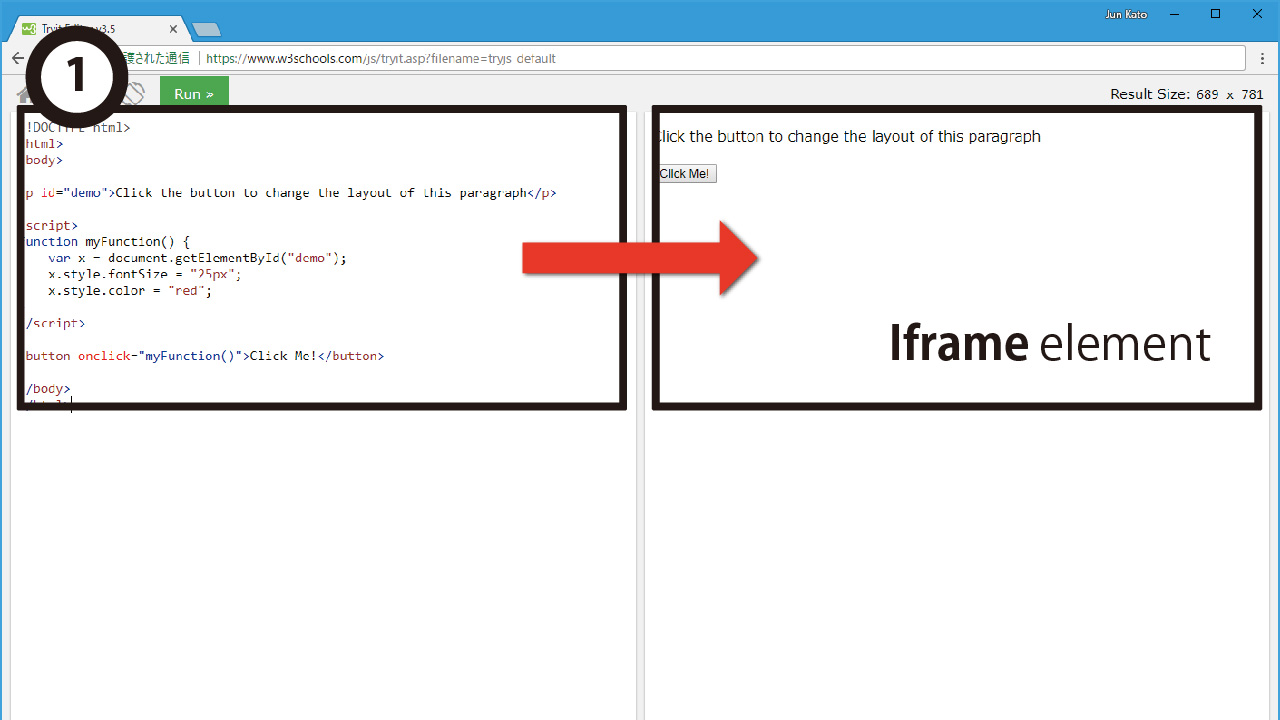

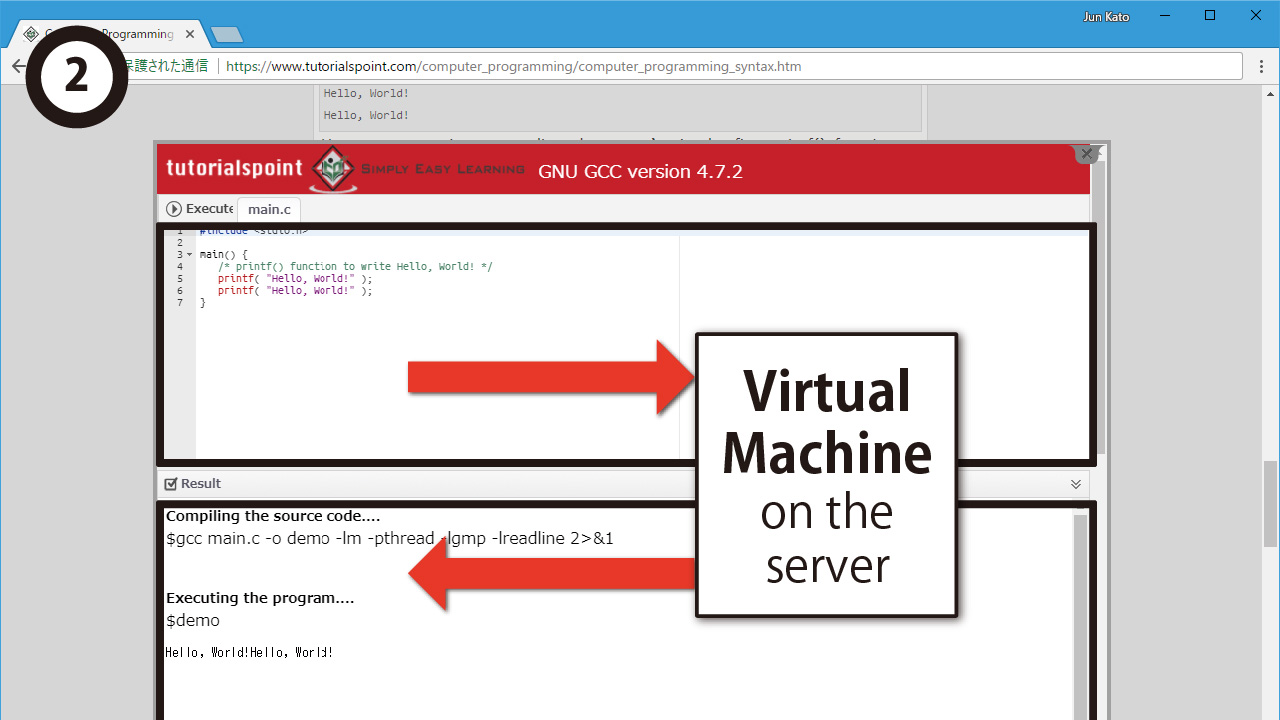

Many of these coding tutorials present read-only content that programmers can read, watch, and sometimes discuss with other learners but cannot interactively run and edit. Examples include API documentations, online fora such as Stack Overflow, and lecturestyle courses provided as MOOCs, such as Coursera and edX. However, there is an increasing number of interactive coding tutorials. Some tutorials take the form of games such as Code Hunt [Bishop et al., ICSE '15] and Gidget [Lee et al., ICER '11] and motivate novice programmers through the gamification of learning. These are designed to enable learners to learn the basics of programming but are not directly connected to the development of actual applications. Other web-based interactive tutorials provide code editors with which programmers can run and edit example code. In terms of the implementation, they can be roughly divided into three categories.

Figure. Three implementation-based categories of interactive coding tutorials

The first category (Figure (1)) is for learning client-side web technologies such as HTML/JavaScript/CSS and utilizes the JavaScript eval() function and/or HTML5 sandboxed inline frames (Iframe). For instance, W3Schools and several other tutorial websites provide a JavaScript code editor next to the preview pane, in which the code gets executed in the Iframe. The eval() and Iframe implementations are very simple and provide quick response to the user edits because the code is executed at the browser’s native speed, but both are vulnerable to malicious code such as infinite loops—when the code executes, the browser can easily crash. Additionally, this category cannot handle programming languages the browser cannot interpret.

The second category (Figure 2 (2)) is for learning how to use the character-based user interface (CUI) and how to build character-based programs, such as for learning Linux command usage and basic C programming. It provides each user access to a lightweight virtual machine (VM) hosted on the server such as a Docker container. For instance, the C programming course in Tutorials Point provides access to the GCC compiler and allows the user to run the program compiled with it. Codecademy provides access to a console of a Linux-based VM and allows programmers to test various CUI commands. npm, the package repository for Node.js libraries, allows the user to test libraries within the browser. In the backend, it utilizes RunKit, which is a platform as a service (PaaS) provider that hosts lightweight VMs capable of running Node.js-based programs. Although this approach is flexible and can safely run any code, it is usually slow because of its high computational cost and the latency between the server and client. To make matters worse, all visitors to the web pages need to share the same computing resources, which are usually limited owing to the running cost, resulting in even slower responses.

Our work and many live programming environments on the web (introduced later in detail) fall in the third category (Figure (3)), in which the user code gets executed in an interpreter. The interpreter is implemented in JavaScript and runs on a web browser. This approach is slightly slower than the Iframe method because of the interpreter overhead but significantly faster than the VM-based method because everything runs on the client computer and there is no network or VM overhead. Because the user code is always executed under the supervision of the host interpreter, malicious code can be detected in a practical manner, and it is much safer than the eval() and Iframe method. The execution is often more controllable than that in the VM method because there is no black box in the code execution process. Our work takes this approach and implements a pseudo-runtime environment that emulates the behavior of a server machine or a microcontroller with a thin interpreter layer and wrapped APIs of a fixed set of libraries.

B. Executable Documents

The usability of API documentation has been extensively studied [Robillard, 2009, Hou et al., ICPC '11, Robillard et al., 2011, Wang et al., MSR '13]. One of the consensuses is that concrete usage information is an important part of the documentation. Executable example codes in API documentations are especially beneficial [Subramanian et al., ICSE '14] because they can be executed when simply copied and pasted to the code editors. Another work enabled inserting such example codes into the code editor by augmenting the code completion user interface [Brandt et al., CHI '10]. Our framework connects the tutorial, example codes edited by the users, and the deployed applications by automatically adding links between these web pages.

Whereas prior work mostly focuses on how to provide better read-only documentation, recent web-based platforms for literate programming, including Jupyter Notebook (formerly known as IPython Notebook [Perez et al., 2007]), allow writing documentation next to the source code and its execution results. Our framework is not designed for literate programming but provides a similar mixed view of documentation and executable code. The difference is that literate programming aims to provide a whole new programming experience, whereas our work aims to help a programmer learn existing programming languages and APIs and develop practical applications that run on common web servers.

Webstrates [Klokmose et al., UIST '15] and its subsequent research Codestrates [Rädle et al., UIST '17] share the philosophy with us, which is about making the development process more visible and sharable as well as the implementation of creating a meta-browser layer within a web browser. While these works provide both runtime and development environments and the applications need to reside within the environments, our framework is designed for tutorials and emulates existing runtime environments so that the applications can run out of the framework.

C. Live Programming on the Web

Live Programming is an emerging field in the intersection of HCI and programming language research with a focus on the fluid programming experience. It aims at eliminating the mental gap between writing code and executing the program to see the results. Because the way to eliminate the mental gap is heavily domain-specific, live programming systems are typically designed to serve specific purposes rather than general programming. For instance, there have been proposed web-based live programming systems for rendering graphics in a massive open online programming training course (such as in Khan Academy’s computer programming course), generating data visualization from tabular data extracted from existing web pages (DS.js [Zhang et al., UIST '17]), producing enclosure layouts for microcontroller applications (f3.js [Kato et al., DIS '17]), authoring videos of lyrics animation (TextAlive [Kato et al., CHI '15]), and improvising music and visual effects (Gibber [Roberts et al., MM '14]).

Given the domain-specific nature of live programming systems, many of them share the pain of transition from managed to wild environments. For example, TextAlive and DS.js are both JavaScript-based live programming environments and applications developed in these sandboxed environments cannot be directly exported as standalone JavaScript projects. This difficulty is a side effect of being domainspecific— these systems provide convenient APIs by default, eliminate the need to write boilerplate code, and sometimes replace part of the coding tasks with GUI interactions such as sliders for parameter tuning. This work aims to retain such benefits and furthermore to provide a feature, named an adaptive boilerplate, to export the projects. The feature transforms the succinct user code into a generic JavaScript project containing boilerplate code.

Top page

Top page